My own experience in a post-World War II work camp, under Communists, convinced me that the evils of Nazi Germany are far from unique. In Romania, where I grew up, the new boss was the same as the old boss. The Soviets picked up where the Nazi’s left off in our embattled country. Stalin wasn’t less horrific than Hitler in his willingness to kill social “undesirables” wholesale. Genocide has been a theme of human history from the start. The list of genocidal leaders is long. Pol Pot, Idi Amin—the roll call runs through thousands of years, and Stalin’s name is one of the most recent. That regime nearly killed me, when I was a child.

So I find it hard to imagine how one could find fault with a project that aims to promote tolerance. But at least one critic has faulted the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles for diminishing the horror of the Holocaust. The museum offers contemporary moral instruction by showing how intolerant behavior today derives from the same streak of cruelty in human nature that gave rise to Hitler’s genocide. In one exhibit, the visitor finds himself in a room with reminders of gay bashing, beatings of Latinos on Long Island, the murder of a Sikh, along with the Federal building bombing in Oklahoma City, as well as 9/11.

Just before you get to the museum’s centerpiece, an exhibit devoted to the murder of six million Jews, you’re led through the Tolerancenter, which attempts to tie together such disparate evils as slavery, prejudice, hate crime and genocide. In this way viewers see bullying in schools as an evil that grows from the same roots as the atrocity of genocide. Edward Rothstein, in The New York Times, found fault with the way this museum links the enormity of Germany’s crime with ostensibly less horrific examples of discrimination and cruelty. There is a mocking tone in the writer’s reaction:

And no Holocaust museum, it seems, can be complete without invoking other 20th-century genocides in Rwanda, Darfur or Cambodia as proof that the lessons of the Holocaust must be taught even more fervently. In the recently opened Holocaust museum in Skokie, Ill., bullying also plays a cautionary role . . . As history, this is laughable. Yet we seem willing to accept that in the case of the Holocaust, an exhibition must allude to all forms of genocide, and must offer broad lessons about tolerance. But what kind of history emerges as a result of these generalizations? History stripped of distinctions.

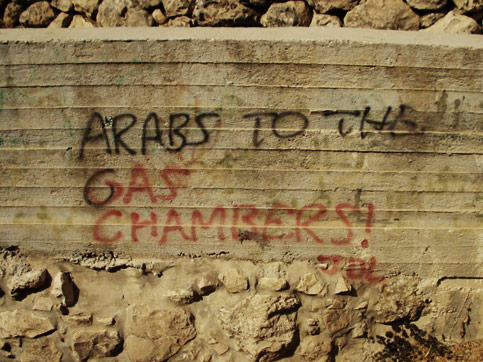

It may be astute to disparage bad history, if that’s what this is, but quit mocking the superficial over-simplifications, and you’ll see an absolutely vital understanding of evil that deserves respect. In its assumptions, and its mission, this museum gets the most important thing absolutely right: evil, in all degrees, grows from human nature and the structure of the brain. We are all wired to be participants in horrors like the Holocaust, because we are predisposed to project our fears onto recognizable threats: we survived as a species by being able to spot the threat and disarm it, either by hunting it down or by fleeing it. Scapegoating is a huge part of this complex set of behaviors. Solidify your tribe by branding the outsiders and banishing them. It happens within the high school halls as well as the concentration camp walls. As a species, we now find ourselves engaging in this kind of behavior when it’s totally unwarranted, because it’s how we’ve been built to react to the world, through evolution.

When our lives are beset by innumerable threats, as was the case for the people of Germany during the economic crisis it faced after World War I, and before World War II, out of chronic fear and anger, we’re more and more likely to project our anxieties onto a group we can scapegoat and then attack. Our brains want us to objectify the threat and eliminate it. Rothstein writes in the Times:

And the deeper one looks at the Holocaust itself, the more unusual its historical circumstances become. The cause of these mass killings was not “intolerance,” but something else, still scarcely understood.

This is mystification and exceptionalism. We can understand the Holocaust, but it requires us to identify with the murderers in a way that Rothstein would find impossible, since he believes that what happened in Germany is a phenomenon that was unprecedented and special, rooted in centuries of European anti-Semitism. What he refused to recognize is that anti-Semitism is simply one among many examples of a potentially genocidal passion that can take root in any heart, anywhere. He may be right that to teach “tolerance” will not prevent a Holocaust from happening again, and that other measures should be explored to make sure it doesn’t. When he expresses disgust that the museum, as well as many other well-meaning and similar efforts, “far from making genocide unthinkable, have helped make it seem as commonplace a possibility as schoolyard bullying” he is actually praising the museum in the highest possible terms. When we realize that genocide is an obscene and horrifying amplification of impulses that are as common as schoolyard bullying, then we’ve begun a process of understanding that evil is universal, a tendency in all of us, and this recognition is the only possible way of preventing atrocities like it from happening again.

This is mystification and exceptionalism. We can understand the Holocaust, but it requires us to identify with the murderers in a way that Rothstein would find impossible, since he believes that what happened in Germany is a phenomenon that was unprecedented and special, rooted in centuries of European anti-Semitism. What he refused to recognize is that anti-Semitism is simply one among many examples of a potentially genocidal passion that can take root in any heart, anywhere. He may be right that to teach “tolerance” will not prevent a Holocaust from happening again, and that other measures should be explored to make sure it doesn’t. When he expresses disgust that the museum, as well as many other well-meaning and similar efforts, “far from making genocide unthinkable, have helped make it seem as commonplace a possibility as schoolyard bullying” he is actually praising the museum in the highest possible terms. When we realize that genocide is an obscene and horrifying amplification of impulses that are as common as schoolyard bullying, then we’ve begun a process of understanding that evil is universal, a tendency in all of us, and this recognition is the only possible way of preventing atrocities like it from happening again.

Do you ever see, in your own life, defensive tendencies—“my team is better than your team,” for example—that show you how tribalism and intolerance begin in everyone’s brain, not simply the most egregious evil-doers?