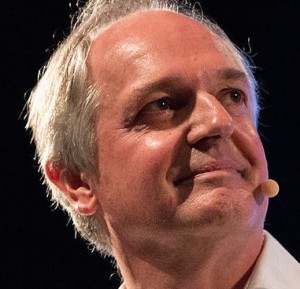

Unilever is one of the largest and most influential companies in the world. Few people would be able to identify what it does, though its brands are household names: Lipton, Dove, Ben and Jerry’s, Pond’s, Vaseline, Ragu, and many many others. It was once called “the world’s most difficult corporate-management job.” The Anglo-Dutch corporation has operations and markets across the globe, and, as a result, has developed over the years close working relationships with governments and NGOs in developing policies that are both good for people and good for business. As non-profit organizations like the World Bank, under Jim Kim’s leadership, study organizational principles that have powered corporations like Ford and Levi Strauss, Unilever’s CEO, Paul Polman, wants his enterprise to adopt a sense of social responsibility normally reserved for the public sector and the non-profits.

Unilever is one of the largest and most influential companies in the world. Few people would be able to identify what it does, though its brands are household names: Lipton, Dove, Ben and Jerry’s, Pond’s, Vaseline, Ragu, and many many others. It was once called “the world’s most difficult corporate-management job.” The Anglo-Dutch corporation has operations and markets across the globe, and, as a result, has developed over the years close working relationships with governments and NGOs in developing policies that are both good for people and good for business. As non-profit organizations like the World Bank, under Jim Kim’s leadership, study organizational principles that have powered corporations like Ford and Levi Strauss, Unilever’s CEO, Paul Polman, wants his enterprise to adopt a sense of social responsibility normally reserved for the public sector and the non-profits.

In my view, we’re at a turning point in world history, approaching a crisis building at many levels: economic, environmental, and political. By making enlightened choices, a business like Unilever, with a market of consumers numbering in the billions can have a profound effect on our future. As The Guardian put it: “Who would have thought even a few years ago that one of the world’s most powerful chief executives would be advocating a transformation in society far more radical than any mainstream politician. Polman . . . says that capitalism needs to be reframed to work for the common good.” What I hear from Polman is an acute insight into this crisis, as he sets an example for all companies in how to navigate through it. A sample of Unilever’s socially responsible strategies as part of a Sustainable Living Planannounced in 2010:

• The plan seeks to double sales and halve the environmental impact of its products over the next 10 years.

• Enhance the livelihoods of millions of people as we grow our business.

• Cut salt, saturated fats, sugar and calories — and rely more heavily in its supply chain on half a million small farm and small scale distributors in developing countries.

Polman doesn’t want this to work only for his own corporation, but to create a new business model others will want to follow, one that is based on the long-term viability of management decisions made right now. It’s the opposite of the short-term shareholder value philosophy that has driven so much of the private sector for decades. What’s intriguing and encouraging to me is that he has grasped one of the core principles of the new economic landscape, which I outlined in The Source of Success: the consumer, the customer, rules everything now. Knowledge and expertise are globalized: competition springs up everywhere, and people can easily choose against any company that doesn’t serve their interests. Whatever is good for that customer, whatever helps the average buyer thrive and succeed, will redound to the benefit of a corporation’s bottom line in good will and loyalty from its buyers. Unilever seems to be building its entire strategry from this fundamental insight.

Polman sees partnership as crucial. Unilever has such a large footprint that it can work in cooperation with the World Bank and the United Nations in establishing policies and corporate practices. If society hopes to change in response to our multi-level crisis, all players need to be on board: not simply governments and NGOs, but the private sector as well. What’s brilliant in his approach, though, is that this arrives not as an obligation but is an opportunity, a chance to emerge with a competitive advantage by first thinking about what’s genuine good for the world, not simply the shareholder. Few CEO’s would admit to being on the phone with Greenpeace on a weekly basis, but Polman boasts about it.

What I find perhaps most encouraging is the way Polman has abolished quarterly reporting of earnings. He wants only investors who care about long-term results, not whatever quick profit awaits around the next turn in the road. Everything he describes, everything he has put in place, has the long term in view, and that’s perhaps the most radical change of all. It’s good for the world. It’s good for the value-conscious investor (in all senses of the word value) and it’s good for someone buying tea or soap. Goodness and profit aren’t mutually exclusive. Rather, they’re utterly inter-dependent. Unilever’s approach is testimony to that.

Polman’s call to action, as he expressed it to The Guardian in 2011, should be framed and hung on the wall of every CEO: “We have increasing income disparity within the developed world. We have a political system that barely functions after the economic and financial crisis. So continuing the way we are going is simply not a solution and increasingly consumers are asking for a different way of doing business and building society for the long term together. We do not have to win at the expense of others to be successful. Winning alone is not enough. It’s about winning with purpose.”