When Andre got off the juvenile court bus at a suburban school, the privileged students there were shocked at what they saw. He and his eight fellow juvenile offenders were wearing neckties. Some of these nine students had been violent criminals, some not. They’d come to this St. Louis suburb, with a police escort, to compete in a chess tournament. Andre was 17, eager to play, but uneasy and unsure about what he was facing. Inside the school, Amy, a little blue-eyed 11-year old girl walked up to him and said: “We will be playing together.” Friendly and fearless, she was half his height. She said, “I want you to know I have never been beaten by an adult.” Then this little chess champion took his hand and skipped off toward the row of chessboards, with Andre in tow, still holding his hand. At the tournament table, they took their seats, and she punched the chess clock. Ten minutes later, he stood up and walked over to Judge Jimmie Edwards, the man who had organized the tournament. “She kicked my butt,” he said. “But she said I was the best adult she’d ever played.” Two hours later, Andre was seated alone, sitting by himself when Amy walked past him. She stopped and asked, “How you doing?” He said, “Not so well.” Immediately, she sat down and began to tutor him. A couple hours passed. When they were done, he went back to the boards, and this time he won.

When Andre got off the juvenile court bus at a suburban school, the privileged students there were shocked at what they saw. He and his eight fellow juvenile offenders were wearing neckties. Some of these nine students had been violent criminals, some not. They’d come to this St. Louis suburb, with a police escort, to compete in a chess tournament. Andre was 17, eager to play, but uneasy and unsure about what he was facing. Inside the school, Amy, a little blue-eyed 11-year old girl walked up to him and said: “We will be playing together.” Friendly and fearless, she was half his height. She said, “I want you to know I have never been beaten by an adult.” Then this little chess champion took his hand and skipped off toward the row of chessboards, with Andre in tow, still holding his hand. At the tournament table, they took their seats, and she punched the chess clock. Ten minutes later, he stood up and walked over to Judge Jimmie Edwards, the man who had organized the tournament. “She kicked my butt,” he said. “But she said I was the best adult she’d ever played.” Two hours later, Andre was seated alone, sitting by himself when Amy walked past him. She stopped and asked, “How you doing?” He said, “Not so well.” Immediately, she sat down and began to tutor him. A couple hours passed. When they were done, he went back to the boards, and this time he won.

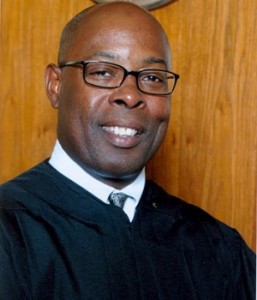

Edwards told this story to his audience at a TED conference two years ago. He said, “An 11-year-old taught my 17-year-old young man how to win and how to lose in less than four hours. She did something that was special. She looked him in his eyes, and she understood that the eyes are the doors to the heart. All of us want to do good in our lives. It’s what we do for others that matters most.”

Edwards has been doing for others for a long time now. A year ago, People magazine named him Hero of the Year for having founded his Innovative Concept Academy. It’s a St. Louis school which serves as a last resort for troubled children under the age of 18. It’s a community effort, representing 45 partners, with an enrollment of 375, offering counseling, recreation and instruction. The building is located in the same gang-ridden neighborhood where Edwards himself grew up in a public housing project.

He takes children who have been expelled, children as young as 11-years-old, sometimes older, sometimes violent. He takes many of the same children he has committed to state correctional facilities in his role as a judge. By showing them he cares about them, he teaches them to care about themselves and others.

As he told his audience: “In our school we have student offices for mental health, for mediation, conflict resolution, for drugs and STDs, in our school is a police department and a K-9 unit where we actually do drug sweeps, not to investigate or arrest, but to ensure these children are in an environment both drug free and safe. We have a uniform policy. They like the uniform. They especially like the tie. The tie, they tell me, make them feel smart. Their teachers respect the tie. Our children work extremely hard. I sentenced their dads and moms to the penitentiary. When the message comes back to me from them, it’s usually mom or dad in jail saying ‘Judge Edwards wants you to behave, and you ought to behave.’

“I ask my children to give me an effort better than yesterday. Then I applaud them. In our school, we take it a step at a time. We have unique programs. Like chess. It’s a deliberate game. You can’t be impulsive. It’s life. See, in chess, you make a bad move, you can lose your queen. In life, make a bad move, you can lose your life.”

Judge Edwards should know. He’s in the business of saving lives. As he puts it: “I truly believe I can rehabilitate children. Most are good and decent. I know they can do better; they can achieve. They want somebody to teach them what’s right.”

Do you know anyone who is as devoted as Jimmie Edwards to helping kids in trouble? Have you worked as a volunteer to befriend or counsel or help young people who need guidance in life? Tell us your story.