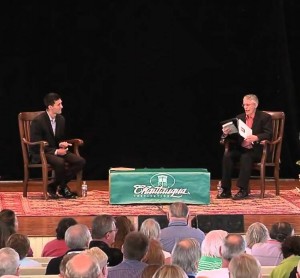

Sometimes doing the right thing is a matter of simply paying attention to an obvious opportunity embedded in what you are doing in your job or daily life — and then having the confidence and courage to make it happen. It’s a matter of ignoring that part of your brain that’s constantly whispering to you, You can’t do that. This is what I took away from a lecture I heard in Chautauqua in 2012 by a father-son duo, Jeff and Josh Nesbit, in which both men astonished me at the impact they’ve had on the world simply by seeing the potential for beneficial change implicit in the work they were already doing.

Sometimes doing the right thing is a matter of simply paying attention to an obvious opportunity embedded in what you are doing in your job or daily life — and then having the confidence and courage to make it happen. It’s a matter of ignoring that part of your brain that’s constantly whispering to you, You can’t do that. This is what I took away from a lecture I heard in Chautauqua in 2012 by a father-son duo, Jeff and Josh Nesbit, in which both men astonished me at the impact they’ve had on the world simply by seeing the potential for beneficial change implicit in the work they were already doing.

Jeff is more or less the guy who killed Joe Camel. That’s how he explained to his son what he’d accomplished at the Food and Drug Administration when he came home from the office one day. It was a long time in the works. In the early 1990s, he almost singlehandedly convinced the FDA to regulate the tobacco industry. He did it simply be becoming a storyteller. As he told his audience at Chautauqua, “We got powerful stories out and in play so that you, the American public, could decide what to do about it.”

As a result of his advocacy, the FDA advertised three stories: 1) Children become addicted to cigarettes after smoking only 10 of them; 2) The tobacco companies were targeting children so that they would become smokers for life; 3) Corrupt scientific findings were used to promote smoking and confuse the issue of whether cigarettes cause cancer. All of this resulted in the sort of regulation that has hobbled the cigarette industry ever since. When Jeff came home to tell his son about how the FDA now had jurisdiction over tobacco, he said, “The FDA killed Joe Camel.”

Josh listened and simply assumed this was the sort of thing it was possible for an individual to make happen. His father showed him how much can be done for other people simply by realizing the potential for good implicit within one’s daily work. As a result, he’s having just as profound an impact on the world as his father did. While still a pre-med student at Stanford, my old alma mater, Josh founded a company that will potentially have an even greater impact on public health than his father’s historic campaign against tobacco. He founded a company called Medic Mobile, which he now runs as CEO. During his sophomore year, for a research project on the HIV virus, he went to Malawi, a landlocked country whose nickname is “The Warm Heart of Africa.” When he arrived at the hospital where he was to do work, he was astonished to see people ox-carting patients to the facility from 100 miles away. He told his Chautauqua audience it became instantly clear to him how a billion people on the planet could go through life without ever once receiving health care.

He noted that the hospital had 500 workers located remotely in surrounding villages. When he visited one of them, it shocked him that his cell phone reception was better there than it had been back in California. He added it up: remote workers equipped with cell phones could provide service to people without the need for travel in most cases. Along with fellow students at Stanford and Lewis and Clark, he got a $5,000 grant form Stanford’s Haas Center for Public Service and collected 100 unused cell phones, and secured FrontlineSMS software to manage cell text messaging in Malawi.

When you break it down that way, step by step, it becomes obvious how possible — I didn’t say easy, but perfectly possible — it becomes to transform a situation for the better if you simply pay attention and act on what you see. Josh distributed cell phones in the villages and solar panels for electricity to power them, which made it possible for the hospital to monitor health in the villages without the need, on either side, for punishing days of travel. His system essentially enables an organization to monitor and organize activities, in real time, in remote locations where there is no Internet connectivity.

What has grown from this ingenious and compassionate project is a company that is currently used primarily to allow medical workers to use mobile phones to gather health data efficiently and assist them with patient follow-up, vaccine adherence, and appointment reminders. The business model is the same as it was at the start: Medic Mobile gathers data on symptoms and transmits medical records through texts. Nesbit hopes, in the future, to partner with UCLA to offer a $15 tool that uses a cellphone’s light and camera to analyze a blood sample for malaria and tuberculosis — essentially turning the phone into a diagnostic laboratory tool. The company is changing lives in 15 countries, including Haiti and Pakistan, though most of its work remains in Africa. Josh Nesbit is only 25, yet he has built a nonprofit with $2.5 million in annual revenue, changing the lives of thousands of people all over the world — all by simply paying attention to the potential for good in what he already knew how to do: send a text message on a cell phone.

A lot of what enabled this father and son duo to help others was their ability to trust in their own skills and determination to change things for the better. Have you had an experience where you recognized a need and saw an opportunity to help another person, or group of people, and ignored that quiet voice of doubt about your ability or authority to step in and take action? I’ve challenged the little voice myself too many times. Can we now commit the next the time we’ll act? Let’s try.